TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

Executive Summary

-

Dually Eligible People and Second-Class Medicare

-

People of Color are Disproportionately Dually Eligible People

— My Case Study of Dually Eligible People in New Orleans -

Second-Class Medicare Violates the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act

-

Second-Class Medicare is Socially Unjust, Morally Wrong, and Fiscally Unwise

-

References

[ ] = hover or tap for footnotes

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

“The COVID-19 pandemic is disproportionately affecting dually eligible individuals, racial and ethnic minority groups, and individuals with disabilities.”

— Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, February 18, 20211

Government policy worsens racial healthcare disparities for low-income dually eligible people.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed racial healthcare disparities for dually eligible people with Medicare and Medicaid — “the elderly and disabled poor”. The Congressional Balanced Budget Act of 1997 worsens these disparities.

The Balanced Budget Act decreases access to health care for dually eligible people.

Medicare beneficiaries worked, paid Medicare payroll taxes, and purchased equal Medicare benefits. Yet the Balanced Budget Act allows poor dually eligible Medicare patients to receive less Medicare benefits than wealthier Medicare patients (“Second-Class Medicare”). As a result, four studies show the Balanced Budget Act decreases access to health care for low-income dually eligible Medicare patients.

The Balanced Budget Act created a Second-Class Medicare system for dually eligible people.

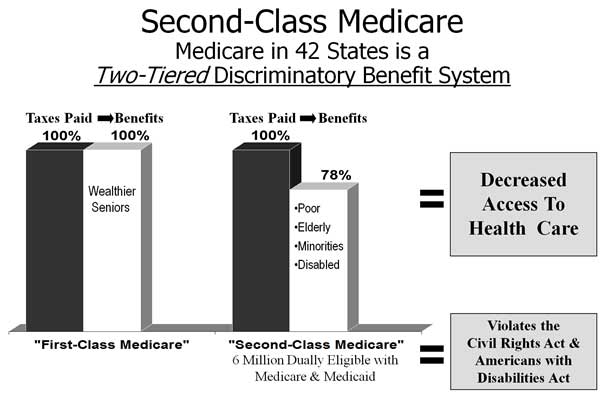

The Balanced Budget Act made it illegal for millions of low-income dually eligible people in 42 states to receive more than 78% of their purchased Medicare benefits. The remaining 22% is uncollectible “Medicare bad debt” — a poverty penalty for poor dually eligible people. Wealthier people receive 100% of their Medicare benefit without paying a poverty penalty. The Balanced Budget Act created a two-tiered discriminatory Medicare system for dually eligible people.

This violates the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Dually eligible people are disproportionately elderly people of color and mentally and physically disabled people. Disproportionately decreasing healthcare access for these groups violates the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act and results in racial healthcare disparities tragically exposed by COVID-19.

Flipping a switch can decrease healthcare disparities for low-income dually eligible people.

Penalizing elderly and disabled poor people for being poor is socially unjust and morally wrong. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pledged to prevent discrimination and promised equal healthcare access for all Medicare patients. It should take only the flip of a legislative switch to reverse healthcare disparities created by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

Conclusion.

Racial healthcare disparities will continue as long as poor Medicare patients receive less Medicare benefits than wealthier Medicare patients.

2

DUALLY ELIGIBLE PEOPLE AND SECOND-CLASS MEDICARE

Dually Eligible People with Medicare and Medicaid — “the elderly and disabled poor” [a]

Dually eligible people (DEP) worked, paid payroll taxes, and earned the right to Medicare, which they receive when they become elderly or disabled. Yet their income is so low that they also qualify for their state’s Medicaid program for the needy.

Dual eligibility is a marker for poverty. DEP are disproportionately elderly, minorities, and mentally and physically disabled people because these groups are poorer than other adult groups in the United States.

DEP are medically frail; one in five DEP lives in a nursing facility.2 The rate of COVID-19 hospitalization and death for DEP is three times greater than the rate of COVID-19 hospitalization and death for non-dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries.3

Of the 62.9 million total Medicare beneficiaries, 12.2 million beneficiaries (19.4%) are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Among DEP, 20.4% are African American, 17.8% are Hispanic, 6.4% are Asian/Pacific Islander, and 0.9% are Native American/Alaska Native.4

DEP are the fastest growing and most expensive Medicare group, consuming one-third of all Medicare and Medicaid finances.5 Their expense is high because the medical cost of being old or disabled is multiplied by the social cost of being poor.

[a] Dually eligible people were identified as “the elderly and disabled poor” by Senator John Breaux of Louisiana in a 1997 report by the US Senate Special Committee on Aging. See: https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/publications/4291997.pdf

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 Created Second-Class Medicare for Dually Eligible People

Following centuries of racially segregated medical care, Medicare promised a single nationwide system of health care that guaranteed equal access for all beneficiaries.[b] The Congressional Balanced Budget Act of 1997 broke that promise.

For DEP, Medicare is “first payer” and sets the allowed payment amount for each medical service. Medicare rarely pays the patient’s entire bill. After the annual Medicare deductible is met, Medicare usually pays 80% of its allowed amount, and the patient, or their secondary insurance, pays the remaining 20% of the allowed amount.

- Before the Balanced Budget Act: For dually eligible patients, state Medicaid agencies generally paid the remaining 20% of the allowed amount when the patient’s medical claim was sent (“crossed over”) from Medicare to Medicaid for payment. With full Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments dually eligible patients received 100% of their promised Medicare benefits.[c]

- After the Balanced Budget Act: To save money for state Medicaid agencies, the Balanced Budget Act permitted states to decrease or stop paying their share of the insurance bill for poor Medicare beneficiaries that crossed over from Medicare to Medicaid. As a result, 42 states now have reduced crossover payments.6

Medicare is an earned benefit with a payment schedule that is usually higher than the payment schedule for Medicaid. The Balanced Budget Act allowed states to pay crossover payments for poor Medicare beneficiaries only up to the lower Medicaid rate. This provision decreased insurance reimbursement for physicians treating dually eligible patients and created a discriminatory two-tiered Medicare system for poor Medicare beneficiaries compared to wealthier Medicare beneficiaries.

In 2018, for example, wealthier Medicare patients and their physicians received 100% of their promised Medicare benefit.[d] But physician reimbursement for 6 million[e] poor dually eligible Medicare patients living in 42 states averaged only 78% of their promised Medicare benefit.7 The remaining 22% of their promised Medicare benefit was uncollectible “Medicare bad debt” — a poverty penalty for DEP with Medicare and Medicaid.

The result of this two-tiered discriminatory Medicare system is that wealthier beneficiaries get access to first-class Medicare, while 6 million low-income beneficiaries get access to second-class Medicare. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 Created Second-Class Medicare for Dually Eligible People with Medicare and Medicaid.

In 42 states, it is impossible — and actually illegal — for physicians treating dually eligible patients to receive 100% of the promised Medicare reimbursement. This is because for DEP, Medicaid is “payer of last resort”: after Medicaid pays its portion of a dually eligible patient’s crossover bill, physicians are forbidden by law from billing or accepting additional money for any unpaid portion of the patient’s bill, including the patient poverty penalty.

As a consequence of the Balanced Budget Act, the “financial value”[f] of a dually eligible Medicare patient in 42 states is, by law, permanently less than the financial value of a non-dually eligible Medicare patient. For DEP, the Balanced Budget Act turned an informal, de facto segregated medical system, into a legal, de jure segregated medical system.

[b] Medicare was born in 1965 as a civil rights bill, part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Medicaid was enacted into law the same year.

[c] With full Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments, (80% of the Medicare allowed amount, paid by Medicare) + (20% of the Medicare allowed amount, paid by Medicaid) = 100% of the promised Medicare reimbursement is received by the physician.

[d] For patients, the Medicare benefit is the ability to access and receive health care. For physicians, the Medicare benefit is the promised financial payment when patients access care.

[e] Math Note 1: Of the 12.2 million DEP, about 60% (7.3 million) are enrolled in traditional fee-for-service Medicare, and about 40% (4.9 million) are enrolled in a Medicare managed care plan or Medicare Advantage plan. Managed care plans and Medicare Advantage plans negotiate private payment schedules with medical providers and offer varying benefits to patients. The effect of the Balanced Budget Act on dually eligible patients in these plans is not known. This report deals only with the approximately 7.3 million dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

Math Note 2: Forty-two of 50 states plus the District of Columbia, or 82% of states, have reduced Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments. Multiplying (82% of states) by (7.3 million DEP in traditional Medicare nationally) shows that about 6 million DEP in traditional Medicare have reduced crossover payments.

[f] A medical office is a business and patients are its customers. In order to treat patients, physicians must keep their medical office open and their staff paid. If a medical office closes because of insufficient income, then the physician, staff, and all patients are harmed.

A Poverty Penalty for Dually Eligible People

A poverty penalty is the additional money poor people pay to purchase goods or services that wealthier people can purchase without a penalty. For example, a poor person without a bank account may pay a $15 “check-cashing fee” to cash a $300 check at a neighborhood store. The $15 fee is a poverty penalty that wealthier people with a bank account do not pay.

DEP in 42 states pay 100% of their Medicare payroll tax yet receive only 78% of their Medicare benefit. The uncollectible 22% of their Medicare benefit is a poverty penalty. Wealthier people receive 100% of their Medicare benefit without paying a poverty penalty.

DHHS Secretary Thompson’s Report Showed Decreasing Crossover Payments Decreases Access to Health Care

In 2003, the Report to Congress by Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson showed the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 decreased access to medical and psychiatric care for poor Medicare beneficiaries.8

According to Secretary Thompson, physicians divide their patient population based on insurance reimbursement and treat higher-paying patients first.[g] When Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments are decreased, physicians treat fewer dually eligible patients and may “stop treating them altogether.” In two-thirds of states studied there was a “dramatic reduction” in psychiatric visits. In Michigan, for example, after crossover payments for dually eligible Medicare patients decreased, access to physician services decreased about 5%, and access to mental health services decreased more than 21%.

The authors of the Secretary Thompson’s study concluded,

Given a choice between a Medicare beneficiary for whom the physician expects to receive 100% of the fee schedule amount, and one for whom the physician expects to receive only 80%, theory predicts that the physician will prefer the first beneficiary. . . . [D]ually eligible Medicare beneficiaries may be a less attractive patient population for providers in many states. . . .

In order to ensure that dually eligible beneficiaries realize the same access to providers as other Medicare beneficiaries, policymakers should consider changing current law. . . . Absent some type of policy change, however, access to Medicare services for dually eligible beneficiaries may continue to decline.9

Additional studies in 2014,10 2015,11 and 201712 confirm that decreasing Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments decreases access to health care for DEP. In the 2015 study, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) acknowledged a “growing compendium of literature suggesting that [decreasing crossover payments] may have the effect of limiting access to primary, routine, and preventative care among [dually eligible Medicare] enrollees.”13

[g] Access to health care varies directly with insurance reimbursement. Wealthy, cash-paying patients get excellent healthcare access. Medicare pays more than Medicaid, so Medicare patients get good access while Medicaid patients get fair access. Uninsured people get poor access. Decreasing insurance reimbursement decreases healthcare access and increases healthcare disparities.

Poverty Penalties and Medicare Bad Debt Greater Than 22%

A dually eligible beneficiary’s poverty penalty and Medicare bad debt can be significantly greater than 22%. The reason is that Medicare does not pay a patient’s medical bill until after their annual Medicare deductible has been satisfied. For 2021, the annual Medicare deductible was $203.

Assume, for example, that the Medicare payment amount for an office visit is $110, while the state Medicaid payment amount for the same office visit is $60. In January of each year, Medicare will pay $0 for this office visit because the patient’s yearly deductible has not been satisfied. The dually eligible patient’s bill then “crosses over” to Medicaid, which pays the physician $60 for the office visit.

In this case, the total Medicare payment of $0 plus the total Medicaid payment of $60 is only 55% of the promised $110 Medicare reimbursement ($60 / $110 = 55%). This leaves the dually eligible patient and their physician with an uncollectible 45% poverty penalty (100% promised – 55% received = 45% poverty penalty or Medicare bad debt).

The dually eligible patient will carry this 45% poverty penalty for two Medicare office visits ($110 x 2 = $220), until the Medicare deductible of $203 has been met. After the deductible has been met, Medicare usually pays 80% of the patient bill, dropping the poverty penalty to 20% for the rest of the year.[h]

[h] For DEP, the payment disparity between the higher Medicare allowed amount and the lower Medicaid payment amount determines the poverty penalty and Medicare bad debt. Payment disparities increase if Medicare payments rise or Medicaid payments fall.

3

PEOPLE OF COLOR ARE DISPROPORTIONATELY DUALLY ELIGIBLE PEOPLE

People of color are disproportionately DEP because they tend to be disproportionately poorer than white people and depend more on Medicaid. Nationally, the percentage of poor dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries who are minorities (47.5%) is more than twice the percentage of wealthier non-dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries who are minorities (21.1%).14

- In Southern states DEP are disproportionately African American. In 2013, African Americans were only 10% of all Medicare beneficiaries in the nation. But they were 19% of all poor dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries in the nation and were 45% of all poor dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries in Louisiana.15

- In Southwestern states DEP are disproportionately Hispanic. In 2013, Hispanics were only 8% of all Medicare beneficiaries in the nation. But they were 12% of all poor dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries in the nation and were 34% of all poor dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries in Texas.16

For any government program based solely on adult poverty, decreasing benefits causes disproportionate harm to elderly people of color and mentally and physically disabled people nationwide.

My Case Study of Dually Eligible People in New Orleans

I practiced internal medicine and geriatrics in New Orleans for 40 years. I had the largest medical practice in Louisiana focused on community-dwelling DEP.[i]

In my 2000 study, 72% or 303 of my Medicare patients in Mid-City New Orleans also had Medicaid and were dually eligible. This percentage (72%) was almost four times greater than the percentage of dually eligible beneficiaries in Medicare nationally (19.4%).

Seventy-nine percent of my dually eligible patients were women; one-third of my dually eligible patients were under age 65 and disabled. Of all my elderly dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid patients, 96% were African American, reflecting the concentrated poverty and racial demographics of many New Orleans neighborhoods.[j]

In 1999 and 2000, I made 78 home visits to DEP. One hundred percent were to African-American patients, all of whom were disabled and homebound with severe medical problems.

In 2000, in response to a budgetary shortfall, Louisiana cut its Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments drastically and warned, “As a result of the rate reduction, some providers may find it necessary to reduce staff or staff hours of work.”17

The new Louisiana Medicare-Medicaid crossover payment for a 45-minute, new-patient

- office visit[k] plunged to 27% of the Medicare rate — resulting in a dually eligible poverty penalty of 73%.[l]

- home visit plummeted to 19% of the Medicare rate — resulting in a dually eligible poverty penalty of 81%.

In response to these Louisiana healthcare cuts, I was forced to make two business decisions, just as Secretary Thompson predicted:

- When Louisiana reduced Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments, I reduced my geriatric clinic office hours by 10% and did other medical work that was not affected by payment cuts.

- When Louisiana Medicaid payment for a home visit collapsed to 19% of the Medicare payment, I stopped making house calls to new dually eligible patients.

I made these unavoidable business decisions to protect my medical practice from severe cuts in income and to keep my staff employed. Sadly, my business decisions decreased healthcare access for 303 poor Medicare beneficiaries who were, disproportionately, elderly African-American grandmothers and mentally and physically disabled people. If the physician next door to me does the same, who is left to treat these frail patients except the expensive emergency room?

[i] Community-dwelling DEP live in the community, and not in a hospital, hospice, or nursing facility. The health status of community-dwelling DEP varies; some have little or no illness, while others are severely ill and bed-bound, requiring total physical care by their family and a home health agency.

[j] On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina destroyed my medical office in Mid-City New Orleans with 7 ½ feet of floodwater. One year later, I opened a new medical office in Central City New Orleans, a neighborhood with concentrated poverty and residential segregation. By December 2007, the post-Katrina racial, gender, and disability demographics of dually eligible patients in my new office in New Orleans zip code 70113 were similar to the demographics at my pre-Katrina office in New Orleans zip code 70119.

[k] CPT, or Current Procedural Terminology, is a set of codes used for billing medical procedures. The CPT office visit code is 99204; the home visit code is 99343.

[l] In 2000 in New Orleans, the promised Medicare reimbursement for office visit CPT code 99204 was $126, while the Louisiana Medicaid payment for the same service was $34. Until the Medicare deductible was met, the total Medicare plus Medicaid payment received by a physician treating a dually eligible patient was the $34 Medicaid payment rate – a loss to the physician of $92 on a single office visit. In this case, ($34 received / $126 promised) is 27% of the promised Medicare reimbursement, resulting in an uncollectible 73% poverty penalty for the dually eligible patient and their physician. After the Medicare deductible was met, Medicare would pay the physician 80% of its $126 promised reimbursement or $101. Since this $101 Medicare payment was already greater than the $34 Medicaid payment rate, Louisiana Medicaid would pay $0 additional crossover payment, leaving a 20% poverty penalty for the dually eligible patient and their physician.

A Worsening Situation for Dually Eligible People

I presented my case study to the New Orleans City Council in 2008[m] and to the Louisiana House and Senate in 2009. At that time, the poverty penalty for DEP in Louisiana was 15%. The City Council and Louisiana Legislature voted unanimously to reject this discriminatory healthcare policy. These rejections were non-binding and did not change Louisiana healthcare policy. Since then, the situation for DEP has worsened:

- From 2004 to 2018, the number of states with reduced Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments increased from 36 states to 42 states.18

- From 2006 to 2018, the proportion of dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries who are people of color increased by 6.5 percentage points, while the proportion of dually eligible beneficiaries who are white decreased by 6.5 percentage points.19

- In 2008, the Louisiana poverty penalty for DEP was 15%; in 2018, the national poverty penalty for DEP was 22%.

[m] To view my New Orleans City Council presentation on YouTube, see:

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=engf65rsOUk

Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ra9uX0-FRGs

4

SECOND-CLASS MEDICARE VIOLATES THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 AND THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT

Minorities and disabled people are protected from discrimination by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

The Civil Rights Act Complaint:

The Balanced Budget Act has a Disproportionate Racial Impact in New Orleans and Elsewhere

In addition to barring intentional discrimination, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 declared that indirect, or disparate discrimination, is illegal. Even if the intent is not to discriminate against any group, if the consequences of a state’s actions have a disproportionate impact on protected groups, then the state’s action is illegal.

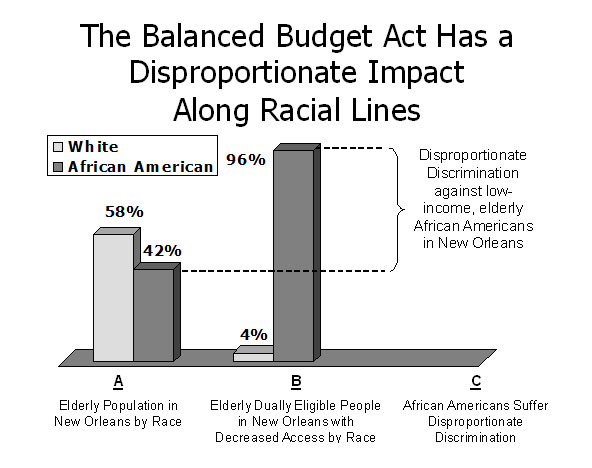

The Balanced Budget Act decreased healthcare access for low-income dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries. Because they are poorer than white Medicare beneficiaries, African-American beneficiaries in New Orleans suffer disproportionate discrimination. See Figure 2.

- Figure 2A. In 1997, African Americans were about 42% of all elderly people in New Orleans 65 years old and older.20

- Figure 2B. Decreasing crossover payments affects only low-income Medicare beneficiaries who also have Medicaid. African Americans depend more on Medicaid than white people because they tend to have lower income than white people. Although African Americans 65 years old and older were 42% of all elderly people in New Orleans, they were 96% of elderly dually eligible patients in my medical practice in Mid-City New Orleans.

- Figure 2C. Secretary Thompson and others showed decreasing crossover payments for DEP decreases their healthcare access. The percentage of elderly African-American Medicare beneficiaries with decreased healthcare access in my medical practice in Mid-City New Orleans (96%) was greater than twice the percentage of elderly African Americans in the New Orleans population (42%).

The consequences of 42 states’ crossover payment reduction are decreased healthcare access and disparate or disproportional discrimination against dually eligible African-American and other minority Medicare beneficiaries in New Orleans and elsewhere. These 42 states are in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Americans with Disabilities Act — the 1st Complaint:

Dually Eligible People Have Disproportionately More Disability than other Medicare beneficiaries

A person who worked and paid taxes has two paths to Medicare eligibility — through age or through disability.[n] Workers younger than 65 years old may be declared disabled by the Social Security Disability Insurance program and become a non-elderly disabled Medicare beneficiary.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits any public program or agency from discriminating against people with disabilities. Poor dually eligible beneficiaries have more chronic illness and more disability than wealthier Medicare beneficiaries. They qualify for even greater protection under the ADA than other Medicare beneficiaries who are not dually eligible.

In 2018, the percentage of poor dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries who qualified for Medicare because of disability (38.6%) was more than four times the percentage of wealthier non-dually eligible beneficiaries who qualified for Medicare because of disability (8.4%).21

- Elderly disabled: Disability increases with age. Many elderly Medicare beneficiaries, and most nursing facility residents, are DEP with multiple chronic illnesses and disabilities; they qualify for protection under the ADA because the ADA has no age limit.[o] By decreasing crossover payments and healthcare access, 42 states are discriminating against millions of dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries who are elderly[p] and who meet the ADA definition of disabled.

- Non-elderly disabled: Any person declared disabled, according to the rigorous standards of the Social Security Disability Insurance program, has already proven that he or she meets the more lenient ADA disability requirements and is therefore covered by ADA legislation. By decreasing crossover payments and healthcare access, 42 states are discriminating against millions of non-elderly dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries who are younger than 65 years old, and who qualified for Medicare by being declared mentally or physically disabled by the Social Security Disability Insurance program.

Providing the least Medicare access for the most disabled people violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.

[n] Disabled individuals under age 65 may qualify for Medicare based on their own work history or they may qualify for Medicare based on the work history of a spouse or parent.

[o] ADA-qualifying chronic illnesses and disabilities common in elderly dually eligible patients and nursing home patients include Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, heart attack, congestive heart failure, emphysema, diabetes, cancer, kidney failure, arthritis, amputation, blindness, deafness, and many others.

[p] Of the 12.2 million DEP in the United States, 7.4 million DEP have Medicare because they are elderly beneficiaries 65 years old or older, and 4.8 million DEP have Medicare because they are younger than 65 years old and disabled. (CMS. Data Analysis Brief)

The Americans with Disabilities Act — the 2nd Complaint:

African-American Dually Eligible People Have Disproportionately More Disability than White Medicare beneficiaries

An African-American Medicare beneficiary is more than twice as likely to be under age 65 and disabled as a white beneficiary.22 Elderly African Americans in the community are 50% more likely to have disability than are elderly white people in the community.23 Elderly African Americans in nursing homes are more disabled than white people in nursing homes and are more likely to have bedsores24 or be in restraints.25

Poverty, disability, and minorities are linked. A government policy that decreases reimbursement for Medicare beneficiaries because they are disabled and poor causes disproportionate harm to dually eligible African Americans.

5

SECOND-CLASS MEDICARE IS SOCIALLY UNJUST, MORALLY WRONG, AND FISCALLY UNWISE

Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane. — Martin Luther King, Jr.26

Concentrated Poverty, Residential Segregation, and Dually Eligible People In New Orleans and Elsewhere

Most physicians have few dually eligible patients in their medical practice. I was able to gather 303 community-dwelling dually eligible Medicare patients in my practice because of concentrated poverty and residential segregation in New Orleans. In New Orleans, poor African Americans are residentially segregated in 47 neighborhoods of concentrated poverty,[q] where 82% of their neighbors are also African American.27

This issue is not limited to New Orleans — the state of Michigan has a 79% white majority, but the city of Detroit is 85% African American, Hispanic, and other minorities28 who are disproportionately clustered in 184 neighborhoods of concentrated poverty.29 Although Michigan is mostly white, the people in Detroit affected by Michigan’s crossover cuts are, disproportionately, elderly people of color and mentally and physically disabled people.

This trend is seen nationwide because most major American cities, including Cleveland, New York, Atlanta, Phoenix, and Los Angeles, have poor, racially and residentially segregated neighborhoods that mirror New Orleans neighborhoods.30 Access to health care is determined locally and varies with neighborhood income. Neighborhoods with concentrated poverty and residential segregation have more DEP but less access to health care. This is true in cities and rural areas across the nation.

[q] Census tracts are proxies for neighborhoods and average about 4,000 people. A census tract with at least a 40% poverty rate is a “concentrated poverty” neighborhood.

Restoring Crossover Payments Will Save Money

Dually eligible patients fill nursing homes. Almost three-quarters (73%) of all Medicare beneficiaries living in a nursing facility are DEP.31 Seventy percent of all Medicaid expenses for DEP goes to nursing facilities and long-term care.32

Access to community physician care for DEP is key to decreasing our nation’s $168 billion nursing facility bill.33 Dually eligible patients have more chronic illnesses and take more medications; they have lower health literacy and more preventable hospital admissions than non-dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries have.

In 2015, CMS confirmed that states with decreased crossover payments had “higher utilization of more acute care services,” including expensive emergency room visits, preventable hospitalizations, and nursing facility admissions.34

Identifying these vulnerable people and improving their access to physician care in the community can save millions of dollars for states and billions for our nation. Restoring crossover payments can help make this a reality.

A Call to Action

Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments allow all Medicare beneficiaries, including low-income DEP, to receive equal Medicare benefits and equal access to health care. By decreasing crossover payments, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 triggered decades of healthcare discrimination for millions of our nation’s most vulnerable people. Failure to end this discrimination will perpetuate racial healthcare disparities tragically exposed by the COVID-19 epidemic.

Medicare beneficiaries worked, paid Medicare payroll taxes, and purchased first-class Medicare benefits. Reinstating full Medicare-Medicaid crossover payments will repair healthcare access, reduce healthcare disparities, and restore civil rights for 6 million elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries. Reinstating crossover payments will save money by increasing neighborhood physician care and decreasing expensive emergency room, hospital, and nursing home care.

The path forward is clear — in its Civil Rights Compliance Policy Statement, CMS pledged to abolish discrimination, remediate past discrimination, and integrate civil rights compliance into CMS programs:

Pivotal to guaranteeing equal access is the integration of compliance with civil rights laws into the fabric of all [CMS] program operations and activities . . . . These laws include: Title VI of the Civil Rights Act . . . [and] the Americans with Disabilities Act . . . . [CMS will] allocate financial resources to . . . ensure equal access; prevent discrimination; and assist in the remedy of past acts adversely affecting persons on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability.35

Racial healthcare disparities have many causes. It will take decades to decrease concentrated poverty, reduce racial and residential segregation, redistribute primary care physicians, and improve health literacy. But it takes only the flip of a legislative switch to restore crossover payments and reverse healthcare disparities created by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

Conclusion

Racial healthcare disparities will continue as long as poor Medicare patients receive less Medicare benefits than wealthier Medicare patients.